OVARIAN CANCER

The incidence of ovarian cancer is rising in Australia – and it is estimated that nearly 1,500 women per year will be diagnosed with this disease by 2018. In general, the risk of getting ovarian cancer is 1 in 70 – however, this could rise to 1 in 2 if you have any significant risk factors or inherited conditions. During your consultation with Dr Salfinger, he will conduct a thorough medical history to determine your specific risks – and advise on any ‘risk-reduction’ preventative surgeries as necessary.

The majority of ovarian cancers are already at an advanced stage when diagnosed, with significant tumour in the abdomen and surrounding tissue. There is no evidence at present that screening for ovarian cancer helps to prevent the disease or increase survival rates – however, screening may be advisable for certain “high risk populations” such as those with a strong family history, gene mutation carriers and Ashkenazi Jewish women.

What are the symptoms

Most patients will have symptoms such as abdominal or pelvic pain, a change in urinary frequency or incontinence, a change in bowel habits, indigestion and unexplained weight gain or loss – as well as more vague symptoms, such as reduced appetite, abdominal bloating & ‘fullness’, fatigue and pressure in the abdomen area.

How it is diagnosed?

Dr Salfinger will conduct a thorough investigation using a combination of examination, ultrasound, CT scans, blood tests and patient medical history. This enables him to accurately assess your condition and choose the best treatment options.

This is particularly important for patients with the above symptoms that persist for longer than a month, and especially if they are over the age of 40 or have a history of ovarian or breast cancer.

Note: not all lumps and cysts in the ovaries are cancerous – some may be benign. To confirm the nature of any mass in the ovaries, it may be necessary to do a special type of biopsy called a “frozen section”, while you are under anaesthetic – this is immediately assessed by a pathologist and the results sent back to Dr Salfinger while you are still in theatre, so that any action required can be taken at the same time, while you are still on the operating table (naturally, following what you and Dr Salfinger have discussed and agreed upon prior to the operation).

How is it treated? What happens during surgery?

There will be different treatment options depending on whether the cancer is only inside the ovaries (in 10 – 15% of cases) or has spread to other areas of the abdomen (in 85% of cases). A decision on whether a surgical approach is best will be made following careful consideration of the patient’s pre-existing medical conditions, as well as discussion at a Multi-Disciplinary Tumour Board Meeting/ Tumour Board Conference between Dr Salfinger and a panel of expert Gynaecological Pathologists and Medical Oncologists.

If the tumour has spread, then the goal will be removing all signs of visible disease, through a procedure known as a debulking operation. In addition to removing the ovaries and uterus, this procedure will also include extensive examination of all the usual places that tumour cells may hide, such as in the lymph nodes, liver, bowel, diaphragm and other abdominal organs.

The gold standard is to achieve “optimal debulking”, which is when no disease is visible and as a Certified Gynaecological Oncologist (CGO), Dr Salfinger’s significant expertise will ensure that there is a high chance of reaching this goal. He will also discuss any available procedures which can help to preserve fertility, prior to surgery.

Will I need chemotherapy or radiation therapy?

In many cases, chemotherapy is a vital part of treatment in the fight against ovarian cancer.

In certain cases, depending on the distribution of the tumour, it may be considered more effective for the patient to undergo a course of chemotherapy first, to reduce the size of tumour, so that surgery has a better chance of successfully eliminating all visible disease. Thus a patient will be given 3-4 cycles of chemotherapy, followed by a less extensive debulking operation, which is then followed by another 3-4 cycles of chemotherapy. This is known as ‘Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy with Interval Debulking’. This has been shown to achieve similar results and rates of survival as initial surgery followed by chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy is usually delivered intravenously (into the bloodstream) but in certain cases, the use of Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy may be considered appropriate. This is when chemotherapy is delivered directly into the abdominal cavity via a special catheter (tubing). Note that it must be used in conjunction with an ‘optimal debulking’ procedure in order to be fully effective. While this technique does produce more side effects at the time of treatment, it confers a survival advantage over intraveneous chemotherapy alone, especially in the case of advanced disease.

What happens after my surgery and treatment?

If you have had a cancer treated, Dr Salfinger will discuss the best follow-up regime, tailored to suit each individual patient. There are normally reviews every 6 months for the first 2 years, extending to 12 monthly reviews for the next 3 years. For patients living outside the Perth Metropolitan Area, Dr Salfinger can make arrangements for ongoing follow-up with your local GP or gynaecologist.

Evidence that regular blood tests and reviews improve outcomes in gynaecological cancers are lacking. However, it may be re-assuring for ongoing follow-up for 5 yrs after the diagnosis. Dr Salfinger will discuss with each patient the recommended tailored to suit your specific needs.

If you have had chemotherapy or radiation after your surgery your follow-up may be shared between Dr Salfinger, the Medical Oncologist or Radiation Oncologist.

The most important to remember is that should there be new symptoms or problems, please contact us so that a review by Dr Salfinger may be arranged.

The majority of ovarian cancers are already at an advanced stage when diagnosed, with significant tumour in the abdomen and surrounding tissue. There is no evidence at present that screening for ovarian cancer helps to prevent the disease or increase survival rates – however, screening may be advisable for certain “high risk populations” such as those with a strong family history, gene mutation carriers and Ashkenazi Jewish women.

What are the symptoms

Most patients will have symptoms such as abdominal or pelvic pain, a change in urinary frequency or incontinence, a change in bowel habits, indigestion and unexplained weight gain or loss – as well as more vague symptoms, such as reduced appetite, abdominal bloating & ‘fullness’, fatigue and pressure in the abdomen area.

How it is diagnosed?

Dr Salfinger will conduct a thorough investigation using a combination of examination, ultrasound, CT scans, blood tests and patient medical history. This enables him to accurately assess your condition and choose the best treatment options.

This is particularly important for patients with the above symptoms that persist for longer than a month, and especially if they are over the age of 40 or have a history of ovarian or breast cancer.

Note: not all lumps and cysts in the ovaries are cancerous – some may be benign. To confirm the nature of any mass in the ovaries, it may be necessary to do a special type of biopsy called a “frozen section”, while you are under anaesthetic – this is immediately assessed by a pathologist and the results sent back to Dr Salfinger while you are still in theatre, so that any action required can be taken at the same time, while you are still on the operating table (naturally, following what you and Dr Salfinger have discussed and agreed upon prior to the operation).

How is it treated? What happens during surgery?

There will be different treatment options depending on whether the cancer is only inside the ovaries (in 10 – 15% of cases) or has spread to other areas of the abdomen (in 85% of cases). A decision on whether a surgical approach is best will be made following careful consideration of the patient’s pre-existing medical conditions, as well as discussion at a Multi-Disciplinary Tumour Board Meeting/ Tumour Board Conference between Dr Salfinger and a panel of expert Gynaecological Pathologists and Medical Oncologists.

If the tumour has spread, then the goal will be removing all signs of visible disease, through a procedure known as a debulking operation. In addition to removing the ovaries and uterus, this procedure will also include extensive examination of all the usual places that tumour cells may hide, such as in the lymph nodes, liver, bowel, diaphragm and other abdominal organs.

The gold standard is to achieve “optimal debulking”, which is when no disease is visible and as a Certified Gynaecological Oncologist (CGO), Dr Salfinger’s significant expertise will ensure that there is a high chance of reaching this goal. He will also discuss any available procedures which can help to preserve fertility, prior to surgery.

Will I need chemotherapy or radiation therapy?

In many cases, chemotherapy is a vital part of treatment in the fight against ovarian cancer.

In certain cases, depending on the distribution of the tumour, it may be considered more effective for the patient to undergo a course of chemotherapy first, to reduce the size of tumour, so that surgery has a better chance of successfully eliminating all visible disease. Thus a patient will be given 3-4 cycles of chemotherapy, followed by a less extensive debulking operation, which is then followed by another 3-4 cycles of chemotherapy. This is known as ‘Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy with Interval Debulking’. This has been shown to achieve similar results and rates of survival as initial surgery followed by chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy is usually delivered intravenously (into the bloodstream) but in certain cases, the use of Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy may be considered appropriate. This is when chemotherapy is delivered directly into the abdominal cavity via a special catheter (tubing). Note that it must be used in conjunction with an ‘optimal debulking’ procedure in order to be fully effective. While this technique does produce more side effects at the time of treatment, it confers a survival advantage over intraveneous chemotherapy alone, especially in the case of advanced disease.

What happens after my surgery and treatment?

If you have had a cancer treated, Dr Salfinger will discuss the best follow-up regime, tailored to suit each individual patient. There are normally reviews every 6 months for the first 2 years, extending to 12 monthly reviews for the next 3 years. For patients living outside the Perth Metropolitan Area, Dr Salfinger can make arrangements for ongoing follow-up with your local GP or gynaecologist.

Evidence that regular blood tests and reviews improve outcomes in gynaecological cancers are lacking. However, it may be re-assuring for ongoing follow-up for 5 yrs after the diagnosis. Dr Salfinger will discuss with each patient the recommended tailored to suit your specific needs.

If you have had chemotherapy or radiation after your surgery your follow-up may be shared between Dr Salfinger, the Medical Oncologist or Radiation Oncologist.

The most important to remember is that should there be new symptoms or problems, please contact us so that a review by Dr Salfinger may be arranged.

ADVANCING THE FIGHT AGAINST OVARIAN CANCER

The number of women diagnosed with ovarian cancer in Australia increased from 833 in 1982 to 1,266 in 2007. 1 An estimated 1,488 women are expected to be diagnosed with ovarian cancer in Australian in 2015. 2 75% of ovarian cancer present at stage III/IV with disseminated abdominal disease and ascites.

Screening

There is NO evidence, at present, that population screening for ovarian cancer is of any benefit in reducing mortality from this disease. Even with combined tumour markers and imaging, overall survival is not improved whilst intervention rates are increased: 10 laparotomies/laparoscopies to find 1 cancer. Screening may have a role in high risk populations with strong family history, gene mutation carriers and Ashkenazi Jewish women.

Initial Cytoreductive Surgery

The amount of residual tumour deposits after surgical management of ovarian cancer has been consistently shown to predict survival. Each 10% increase in maximal cytoreduction was associated with a 5.5% increase in median survival time. 3 With 75% of this disease presenting at stage III/IV with ascites and abdominal deposit on bowel, liver, diaphragm and other abdominal organs, surgery to achieve optimal debulking may be radical, extensive and potentially morbid. This surgery, in addition to the removal of the ovaries and uterus, often involves a bowel resection, omentectomy, diaphragmatic and subsegmental liver resection. Decision whether a patient is a candidate for such a surgical approach should be derived after careful consideration of her other co-morbidities and discussion in a multidisciplinary meeting. Optimal debulking to nil macroscopic visible disease in selected patients remains the gold standard of care in ovarian cancer patients.

Screening

There is NO evidence, at present, that population screening for ovarian cancer is of any benefit in reducing mortality from this disease. Even with combined tumour markers and imaging, overall survival is not improved whilst intervention rates are increased: 10 laparotomies/laparoscopies to find 1 cancer. Screening may have a role in high risk populations with strong family history, gene mutation carriers and Ashkenazi Jewish women.

Initial Cytoreductive Surgery

The amount of residual tumour deposits after surgical management of ovarian cancer has been consistently shown to predict survival. Each 10% increase in maximal cytoreduction was associated with a 5.5% increase in median survival time. 3 With 75% of this disease presenting at stage III/IV with ascites and abdominal deposit on bowel, liver, diaphragm and other abdominal organs, surgery to achieve optimal debulking may be radical, extensive and potentially morbid. This surgery, in addition to the removal of the ovaries and uterus, often involves a bowel resection, omentectomy, diaphragmatic and subsegmental liver resection. Decision whether a patient is a candidate for such a surgical approach should be derived after careful consideration of her other co-morbidities and discussion in a multidisciplinary meeting. Optimal debulking to nil macroscopic visible disease in selected patients remains the gold standard of care in ovarian cancer patients.

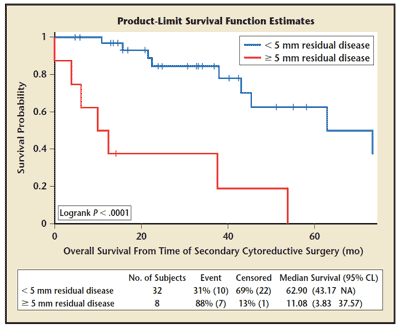

Figure 1. Overall survival of secondary debulking by amount of residual disease. CL, confidence limits; NA, not applicable. Reprinted from International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Vol. 108, Schorge JO et al, “Secondary cytoreproductive surgery for recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer," pp. 123-127, Copyright 2010, with permission from Elsevier.

Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy

Adjuvant chemotherapy traditionally have been administered intravenously, however recent randomized studies have shown that combination intravenous and chemotherapy delivered via a port directly into the abdominal cavity achieves better progression free (18.3 vs 23.8 months P=0.05). and overall survival (49.7 vs 65.6 months P=0.03). 4 This improvement in survival only applies when initial cytoreductive surgery have achieved an optimal debulking with no residual disease >1cm. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy produces more side effects at the time of treatment when compared to intravenous only treatments, but quality of life was equal at 12 months after treatment.

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy with Interval Debulking

In patients whom we predict may not achieve optimal debulking in the initial cytoreductive surgical effort, neoadjuvant chemotherapy should be strongly considered. This approach, 3 cycles of chemotherapy followed by interval debulking and then completion 3 cycles chemotherapy has been shown to achieve similar progression free and overall survival with less morbidity. 5 Initial treatment with chemotherapy may reduce tumour burden, to allow less radical surgery to achieve optimal debulking. Complete resection of all macroscopic disease, whether performed as primary treatment or after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, remains the objective whenever cytoreductive surgery is performed as complete resection of all macroscopic disease (at primary or interval surgery) was the strongest independent variable in predicting overall survival.

Targeted Therapy

Any use of targeted therapy for ovarian cancer is still classified as experimental and not standard. Whilst trials are still underway, evidence is slowly

emerging that there are several classes of drugs that may be effective against ovarian cancer.

Chemotherapy with angiogenesis (growth of blood vessels) inhibition drugs such as Bevacizumab in preliminary studies show it may improve progression survival but not overall survival from ovarian cancer. 6

PARP Inhibitors may have some utility in ovarian cancers related to the BRCA mutation. 7

Ongoing Follow-up

There is little evidence to suggest that intensive follow-up of any gynaecological cancers improve outcomes. This is counter-intuitive as from basic principles, one would think that earlier detection of recurrences may improve outcome.

Certainly there is no role of frequent CT scans, as radiation from CT scans may be harmful. A recent large multi-centre randomized control trial compared whether to follow-up ovarian cancer patients who are asymptomatic, with blood tumour markers or not. 8 It showed that patients followed up with routine blood tumor markers lived just as long as those who did not have frequent blood tests, but those who did have the blood tests, had a poorer quality of life. Patients who had regular blood tests discovered recurrence earlier but despite earlier re-treatments with chemotherapy, there was no survival advantage, but led to more side-effects and hence poorer quality of life.

Certainly there are some limitations to this study, including the non-utility of secondary debulking surgery. These patients were mostly re-treated with chemotherapy only without surgery. And secondary optimal debulking surgery prior to further chemotherapy for recurrent disease has been shown to improve survival compared to chemotherapy alone.

Dr. Salfinger will discuss individually with each cancer patient to come up with a follow-up regime which is best suited.

Adjuvant chemotherapy traditionally have been administered intravenously, however recent randomized studies have shown that combination intravenous and chemotherapy delivered via a port directly into the abdominal cavity achieves better progression free (18.3 vs 23.8 months P=0.05). and overall survival (49.7 vs 65.6 months P=0.03). 4 This improvement in survival only applies when initial cytoreductive surgery have achieved an optimal debulking with no residual disease >1cm. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy produces more side effects at the time of treatment when compared to intravenous only treatments, but quality of life was equal at 12 months after treatment.

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy with Interval Debulking

In patients whom we predict may not achieve optimal debulking in the initial cytoreductive surgical effort, neoadjuvant chemotherapy should be strongly considered. This approach, 3 cycles of chemotherapy followed by interval debulking and then completion 3 cycles chemotherapy has been shown to achieve similar progression free and overall survival with less morbidity. 5 Initial treatment with chemotherapy may reduce tumour burden, to allow less radical surgery to achieve optimal debulking. Complete resection of all macroscopic disease, whether performed as primary treatment or after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, remains the objective whenever cytoreductive surgery is performed as complete resection of all macroscopic disease (at primary or interval surgery) was the strongest independent variable in predicting overall survival.

Targeted Therapy

Any use of targeted therapy for ovarian cancer is still classified as experimental and not standard. Whilst trials are still underway, evidence is slowly

emerging that there are several classes of drugs that may be effective against ovarian cancer.

Chemotherapy with angiogenesis (growth of blood vessels) inhibition drugs such as Bevacizumab in preliminary studies show it may improve progression survival but not overall survival from ovarian cancer. 6

PARP Inhibitors may have some utility in ovarian cancers related to the BRCA mutation. 7

Ongoing Follow-up

There is little evidence to suggest that intensive follow-up of any gynaecological cancers improve outcomes. This is counter-intuitive as from basic principles, one would think that earlier detection of recurrences may improve outcome.

Certainly there is no role of frequent CT scans, as radiation from CT scans may be harmful. A recent large multi-centre randomized control trial compared whether to follow-up ovarian cancer patients who are asymptomatic, with blood tumour markers or not. 8 It showed that patients followed up with routine blood tumor markers lived just as long as those who did not have frequent blood tests, but those who did have the blood tests, had a poorer quality of life. Patients who had regular blood tests discovered recurrence earlier but despite earlier re-treatments with chemotherapy, there was no survival advantage, but led to more side-effects and hence poorer quality of life.

Certainly there are some limitations to this study, including the non-utility of secondary debulking surgery. These patients were mostly re-treated with chemotherapy only without surgery. And secondary optimal debulking surgery prior to further chemotherapy for recurrent disease has been shown to improve survival compared to chemotherapy alone.

Dr. Salfinger will discuss individually with each cancer patient to come up with a follow-up regime which is best suited.

References:

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & Australasian Association of Cancer Registries 2010. Cancer in Australia: an overview, 2010. Cancer series no. 60. Cat. no. CAN 56. Canberra: AIHW

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2010. Gynaecological cancer projections 2010-2015. Cancer series no. 53. Cat. no. CAN 49. Canberra AIHW.

- Bristow et al. Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: a meta-analysis. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (2002) vol. 20 (5) pp. 1248-59

- Armstrong et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. New England Journal of Medicine (2006)

- Vergote et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. The New England journal of medicine (2010) vol. 363 (10) pp. 943-53

- Burger RA, Brady MF, Bookman MA, et al. Phase III trial of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of advanced epithelial ovarian cancer, primary peritoneal cancer, or fallopian tube cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 2010;18s:946s (LBA 1).

- Chan and Mok. PARP inhibition in BRCA-mutated breast and ovarian cancers. Lancet (2010) vol. 376 (9737) pp. 211-3

- Rustin et al. Early versus delayed treatment of relapsed ovarian cancer (MRC OV05/EORTC 55955): a randomised trial. Lancet (2010) vol. 376 (9747) pp. 1155-63